Written by Ian Francis

I visited Eric Turland at his home in Poole in the late summer of 2022. A proud Brummie, he was still basking in the glow of the Commonwealth Games and happy to see his hometown showing its best side on national telly. On the eve of his 98th birthday it was a privilege to spend some time with ‘Britain’s oldest living cinema organist’, and I was keen to get a sense of what the job was like. In many ways the cinema organist was the last remnant of the army of musicians who used to accompany films before the advent of talking pictures. Still playing beyond the war and well into the 1960s, these suited gents – the vast majority were gents – would perform during the interlude every evening, as well as supplying the tunes for special events and kids matinees. I began by asking Eric how he got into music.

"My dad was an insurance agent so we moved around a fair bit when I was young, from Northamptonshire to Stirchley to Bromsgrove. I passed my grade one piano there, and then my dad got moved down to Vale of Evesham. There was no music teachers in Wyre Piddle where we lived but the organist of Pershore Abbey gave piano lessons. Then one year we went to Blackpool for the illuminations. We went in the Tower Ballroom, and I saw this fella Reginald Dixon playing the organ. I vividly remember to this day saying to my parents, 'that's what I'm going to do when I grow up. I'm going to play one of them.' And they look at you: 'Yes, yes, of course you are Eric, yes.' Anyhow, I told the organist of Pershore Abbey that I'd got interested in the organ and he started showing me a few tips. And when I was 14 I got a job as organist at this little village church, while I was still at school.

When I left school I got a job in Worcester, which was 10 miles away from where we lived. And one dinner time I plucked up courage to go to the Gaumont cinema - I was only 15 at the time. I said 'is the organist available?' And they said yes. I said, 'can I have a word with him?', they said yeah. I said, 'Do you give organ lessons?' He said yes. And he told me how much they were, which was a bit of a shock. I went home and told my parents and they said 'forget it'. Anyway, they must have told my uncle, and my uncle paid for me. I think it was about 13 guineas for a term of 13 lessons, something like that. The organist asked 'Do you want to take it up as a professional?' and I said, 'Well, I'd like to.' So he said 'at the end of the 13 lessons, I'll tell you whether it's worth your while carrying on.' After that he said, 'Oh yes, you've got talent and ability. Have another term, and we'll go from there.' During the second term he let me play over dinner time, when the audience was coming in. At the end of the 13 lessons he asked if I still wanted to take it up as a job. He said 'Gaumont British aren't starting new organists due to the war, but ABC and Odeon are - do you want me to get you an audition with one of them?', and I said 'yes please.'

So I had an audition with ABC at the Pavilion cinema in Stirchley. After five minutes, the organist said, 'Okay, that's enough.' And I thought, oh that's it then. I've had it obviously. Anyhow, a fortnight later I had a letter from ABC headquarters, offering me the post of resident organist at the Piccadilly Cinema, Sparkbrook, Birmingham. So I immediately gave my notice in where I was working, and another fortnight later I was in Birmingham."

This was in April 1942, a time when the city was a regular target for German bombing raids. Typically Eric was more concerned about the threat to his instrument than his life.

"I enjoyed my time at the Piccadilly. The only problem was we used to get bombed because we weren't far from the BSA works, which made munitions at the time. A landmine landed opposite the Piccadilly in Alfred Road, blew all the doors of the cinema in, and affected the organ. About six of the pedals wouldn't play. An electrical firm used to keep coming in and trying to get it going, but it never worked properly again.

My working day was very unsociable hours: first thing in the morning, till the cinema shut at night. In those days it was continuous performance, once the doors opened at say, 1.30pm, they didn't shut them till 11 o'clock. So if you were that way inclined and you liked the film, you could sit there all day, so long as the usherette didn't catch you. I used to have to play from 1.30 till 2 o'clock. At six o'clock we had to put on a monkey suit, and stand in the foyer to welcome the patrons. In them days, the cinemas were packed every night. And then I used to have to play in between the films, because we'd have a B feature - a cartoon, a documentary, a travelogue or something like that. The news, and then the big film: the A film. I used to have to link all those together. If there was time, if it was a longer film, they used to give me an organ interlude. And then it was a sackable offence if you weren't there to play the national anthem at the end."

Eric (left) in the record library in Basra in 1946.

Pavilion staff photo, 1947. Eric is on the front row, third from the right.

Musical interlude at the Pavilion in 1947. Eric is on the Christie.

Pavilion staff Christmas party, 1947. Eric and Lilian are in the third row on the right hand side.

Eric used to squeeze in extra bits of work where he could, whether it was playing piano in a dance band at the Balsall Heath Institute or night shifts fire-watching at the cinema. Then as soon as he turned 18 he had to sign up for the army, and by the end of 1942 he was stationed in Omagh doing his basic training. “I wasn’t really one for running about with a rifle, sticking bayonets in dummies, so I applied to join the stretcher bearers.” After medical training and various postings around England he found himself sailing to Italy in early 1944, landing in Naples after three weeks. “I enjoyed Italy. I didn’t enjoy the fighting, but I enjoyed the country.” Eric’s unit were soon involved in Monte Cassino, one of the war’s bloodiest battles, and following months of action they moved north to Rome.

"Irrespective of what the Americans tell you, we liberated Rome. And because it was an open city, there was no bombing or shelling or fighting. We just went in one end as the Germans went out the other, and we got up as far as Bologna. Then after a few weeks leave in Rome we went down to Taranto on the heel of Italy, got on a boat and landed up in Port Said in Egypt. We were given the opportunity of having leave in Cairo or Alexandria, and I chose Alexandria because it's by the sea and I like living by the sea. Unfortunately after about a week, I contracted jaundice and while I was in hospital my unit went back to Italy. When I was due to go back to my unit, they give you a medical before you go back, and they downgraded me from A1 down to B1, which meant I was unfit for active service. They said I was what they call bomb happy or shell shocked, so they kept me on in this convalescent camp. I worked in the orderly room, and played the piano in the dance band there."

This led to a stint with forces radio in Basra after the war ended, first in the record library and then playing Benny Goodman and Frank Sinatra requests for troops in the Middle East. When Eric was finally demobbed in 1947 he dusted off his monkey suit, this time playing at the Pavilion Cinema in Stirchley: “At first I didn’t enjoy it as much as the Piccadilly – they were more of a toffee-nosed audience, if you get what I mean.” With cinema admissions still buoyant in the late 40s, there was a lively social scene for those working in picture theatres. By this point Eric’s father had followed him into the business, assistant managing the Oak in Selly Oak, and there were regular get-togethers with the other five ABC organists in the area. He also had a friend who managed the Beacon in Smethwick, and one evening he was asked to play piano at the cinema to complement a new release called The Jolson Story. He got talking to a woman on the cash desk, and the following year Eric and Lilian were married. Back at the Pavilion, he was kept occupied with interludes, promotional gimmicks and kids matinees. As for most ABCs, one of the busiest times of the week was Saturday morning when a thousand kids would descend on the cinema for the ABC Minors Club.

"We had about 50 ABC Monitors. And every week, we used to take them down in the basement and give them a party. We'd give them jelly and ice cream and stuff like that, and give them their orders for the Saturday morning. Then on the day it was bedlam. I used to get ice cream cartons thrown at me. The organ was a Christie, and it was up on the right hand side of the stage, which was quite a job to get to because you had to go through a door on the left hand side of the cinema, and walk right across the stage behind the screen, so nobody could see you trying to dodge girders and this that and the other. If I did an organ interlude, you had to think of something, you know, a simple singsong kind of thing. You had to send away slides with all the words on, and you had to rehearse it with the operators. I had a bell on the organ, and I used to press this bell to change the slide."

The ‘Pav’ was a suburban picturehouse and didn’t get too many big stars visiting, but Eric does remember Richard Attenborough appearing at a showing of Brighton Rock in 1948. “And the manager said to me ‘Can you take Mr Attenborough up to the cafe and buy him a coffee and a cake or something?’ Because he wasn’t very well known was he, it’s only his second film. So I took him up to the cafe, bought him a cake and coffee. It was a Saturday evening, and he suddenly said to me, ‘Is there a shop round here I can get a sports paper?’ I said, ‘Yeah, why?’ ‘I want to see how Chelsea got on.’ So I got one of the doormen to go out and get him this paper from the newsagent opposite. He was ever such a nice fella.”

By 1950 film attendances were beginning to drop and it was clear that the cinema organist’s days were numbered. “I had the chance of a job at Cadbury’s playing the organ in the concert hall there and I thought, right, that sounds a bit more sensible. Well, the hours were more sociable. And if I stay at the Pavilion, I’m going to be out of work in a couple of years’ time. I could see which way the wind was blowing.” He traded a drop in income (“from eight pounds a week to five and something”) for a steadier life at Cadbury, although he would carry on playing for the ABC Minors on a Saturday. Then in 1953 the Pavilion’s organ had to make way for a larger screen, and – aside from the occasional one-off gig – Eric’s cinema days were over.

Lilian also worked at the chocolate factory, packing Wispa bars, and when they both retired in the early 80s they decided to move to the south coast. Sadly Eric lost Lilian in 2001, and he has stayed on in the same house in Poole. In the spare bedroom there’s a Hammond organ he bought for himself from Lewis’ department store as a retirement treat, and although his health is not brilliant these days he still plays when he can; if the kids in the neighbourhood have a birthday, he will ring them up and play ‘Happy Birthday’ down the phone. As a parting gift I gave Eric a miniature of the Piccadilly for his mantelpiece: “it’s just like the real thing, except this one’s still got the doors on it.” Film only accounted for a small part of Eric Turland’s working life, but as for many others we spoke to it was clear that his cinema experiences had shaped him for good.

Eric in his band uniform in 1942. His mother sewed his initials onto it.

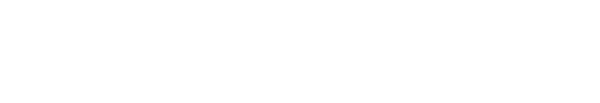

Eric standing outside the Pavilion in 1947.

Eric at home in Poole in 2022, with miniature Piccadilly.

"There's nothing I liked better than going in on a morning into an empty cinema. The cleaners were there. We used to have an old Irish woman called Mrs Marshall who was the chief. 'You come to play that old tin can again have ya?' I'd give her 'When Irish Eyes Are Smiling' or 'Mountains of Mourne' or summat, and she was happy. I enjoyed my job. I really did."