Wonderland researcher Shelley Budgeon reflects on the common threads in three oral histories about formative film experiences.

The social and cultural significance of cinema reaches far beyond its role as a form of entertainment. Going to the cinema provides the opportunity to be transported to distant places; to be fascinated by the lives playing out across the screen; and to perceive our world in a different way. Setting out to capture such dimensions, the Wonderland project explored the numerous ways that Birmingham’s cinema history is also a personal history – a multi-layered story about the chaotic fun of children’s Saturday morning picture shows, the fond reminiscence of a special night spent sitting on the balcony, or a recollection of the thrill of being star struck. In a series of oral history interviews these kinds of moments were recounted, illuminating the special place going to the movies has occupied in many people’s lives. In particular, the centrality of cinema within the life of Birmingham’s working-class communities such as Tile Cross, Hockley, and Small Heath emerged in these personal histories. Every neighbourhood had at least one local cinema and going to the movies played an integral part in the rhythm of weekly life. These stories reveal several key themes that help us to understand how Birmingham’s cinemas were experienced and their enduring significance.

Firstly, the cinemas frequented by interviewees were described as spaces where they encountered images and ideas that impacted deeply on how they understood their place in the world. This was an experience defined by a sense of release from the mundane reality of daily life.

"The cinema was well affordable and I think it was really a big influence on working class people cos I think the cinema showed people things and made them think, ‘oh I could do that’. About eating and drinking, I mean about all sorts of things and clothes - so it was a role model wasn’t it because if you came from, which we did, the inner city slums, we hadn’t got many role models because we never went to the theatre or anything like that, so the cinema really showed you what you were missing. Oh I loved the cinema."

[going to the cinema with friends] "that was pretty formative, and I imagine that for most working-class kids from a relatively, I wouldn’t say we were poor but we weren’t well off - we didn’t have a bathroom or a television. That was the space you went to and felt free, I guess. I do remember just the sheer joy of it. Just that general sense of fun."

Secondly, memories of going to the cinema were animated by the physical characteristics of the buildings themselves and their geographical location. A colourful picture of their place within the landscape of the community emerged in the detailed accounts of the streets where these cinemas stood, their unique architectural features, and the journeys taken by bus or by foot to get there.

"There were two cinemas - The Palladium and The Villa Cross, within spitting distance…they were the two we went to all the time because they were in walking distance of where we lived. It was great. I loved going to the movies. And also it was very comfortable. Those velvety seats. We didn’t have anything like that in our house. I mean we weren’t dirt poor but we were poor by today’s standards. So it was comfortable and it was warm and I think that for a lot of people that was why they sat through two performances, cos it was warm."

The cinemas of the older generations were described as providing rather basic amenities. In contrast, however, those associated with the golden age of the 1930s were remembered for their grandeur. These picture palaces, embedded within the local neighbourhood, were very much part of the community and yet they also provided a separate, special space marked out from their immediate surroundings.

"When you went in, there was the carpet, but I remember the feeling of the seats, they were velvet but very rough. When you pulled them down, they were rough with hard padding. There was something about that… For older generations they would have been more basic, ‘flea pits’ with cheap seats. We would have sat downstairs. Sitting in the stalls was normal but sitting in the circle, that would have been special - a treat! Oh I can feel it now! When you go to a multiplex now you don’t get that sense of the building…"

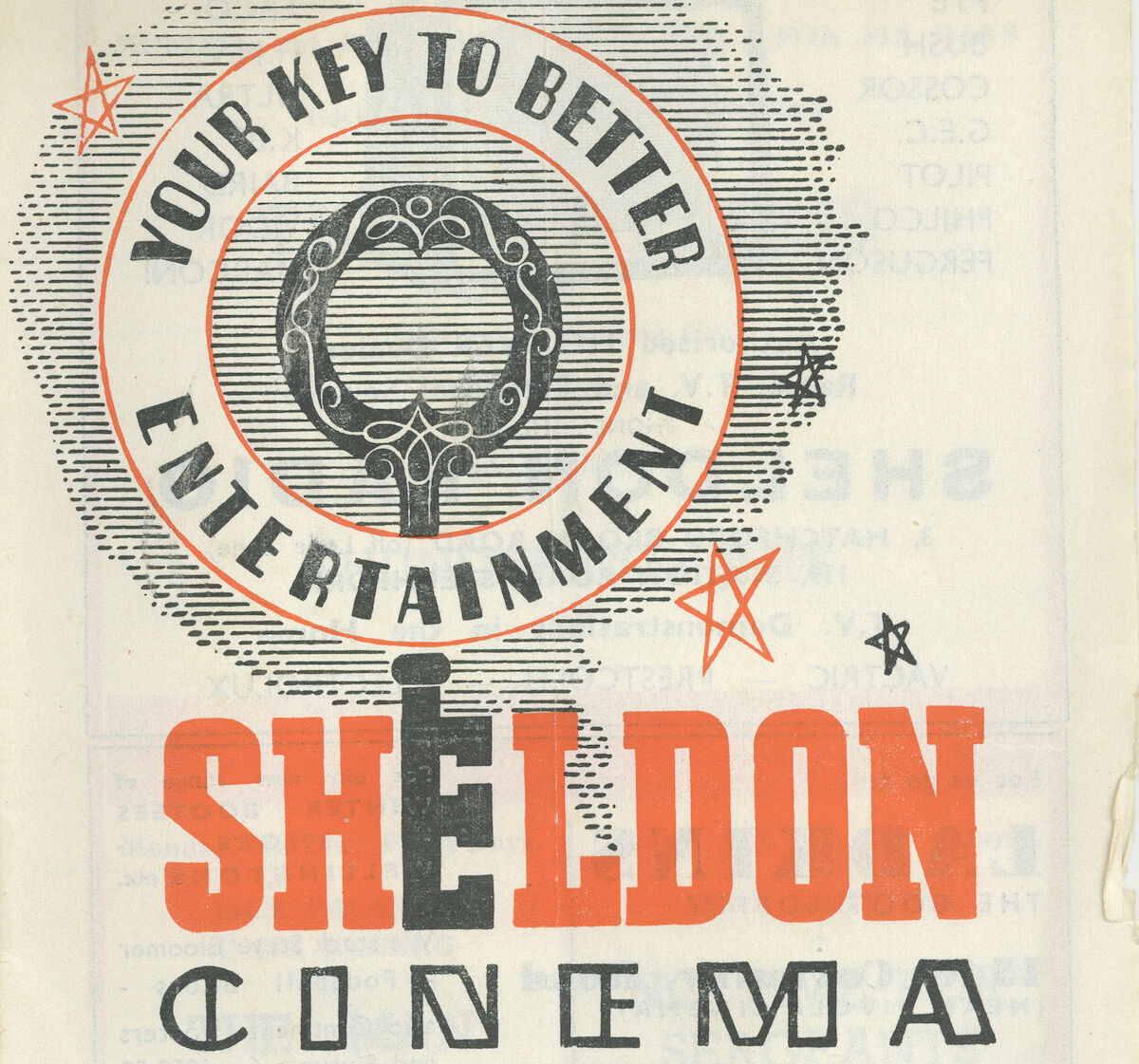

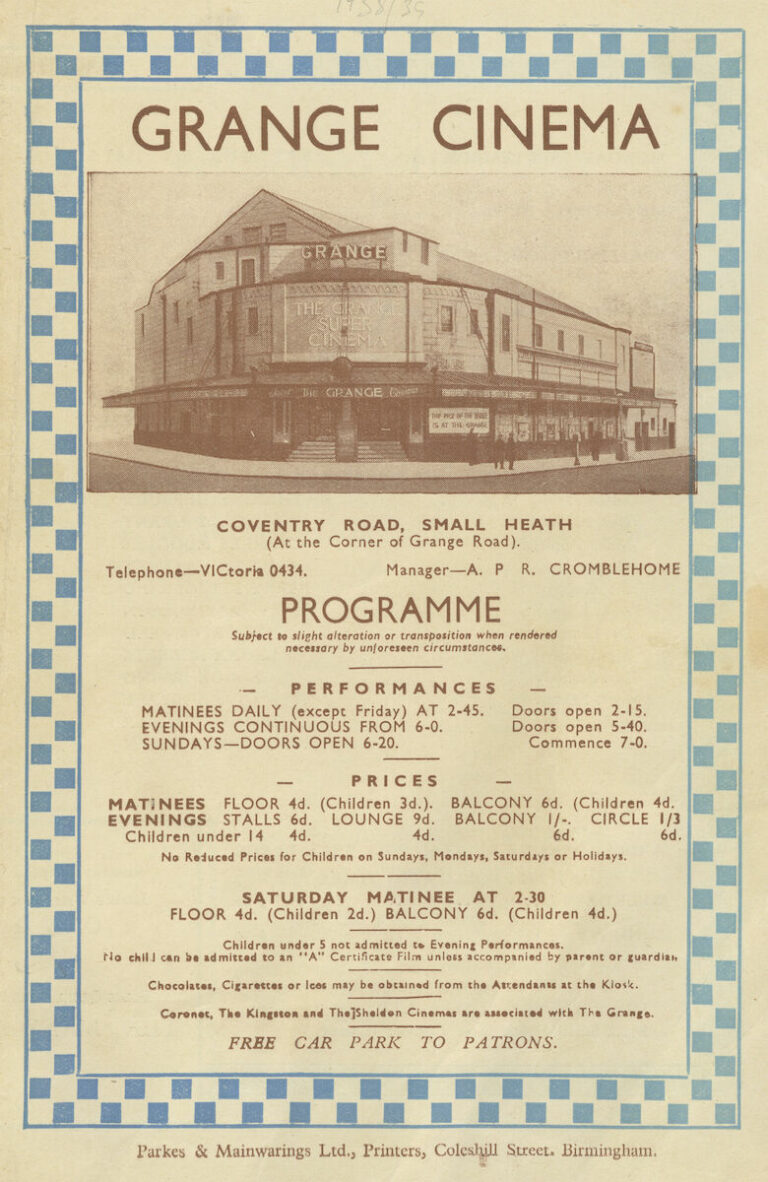

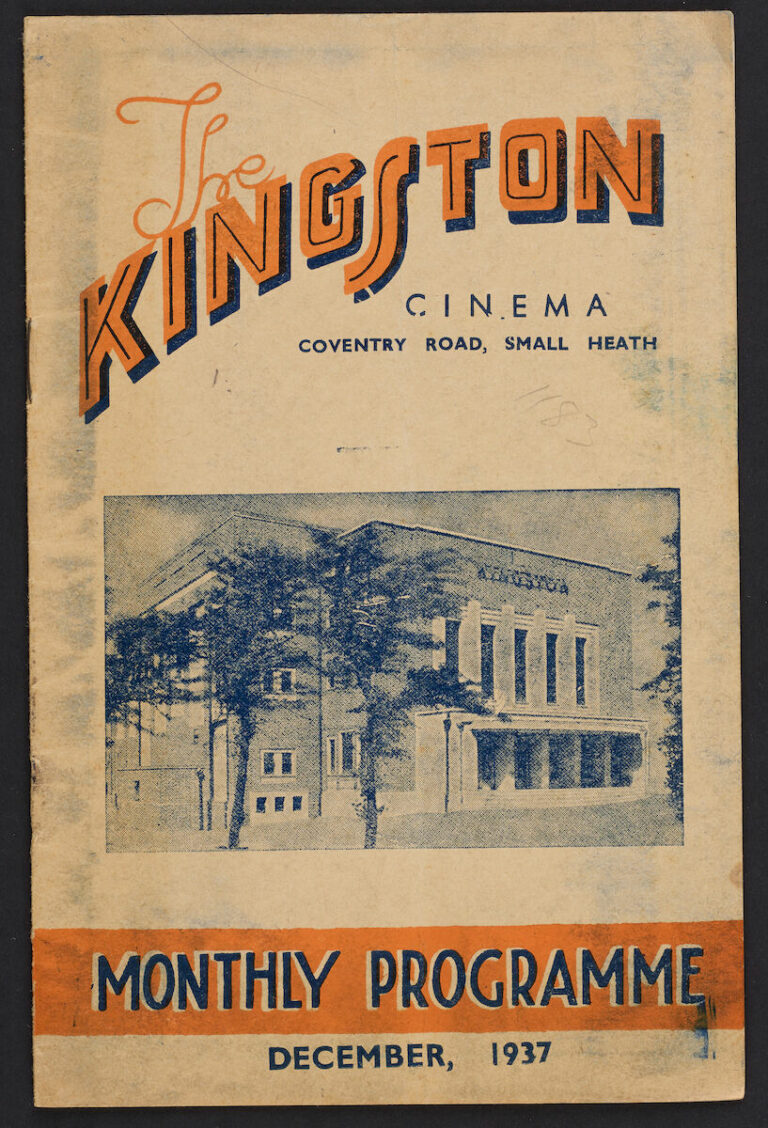

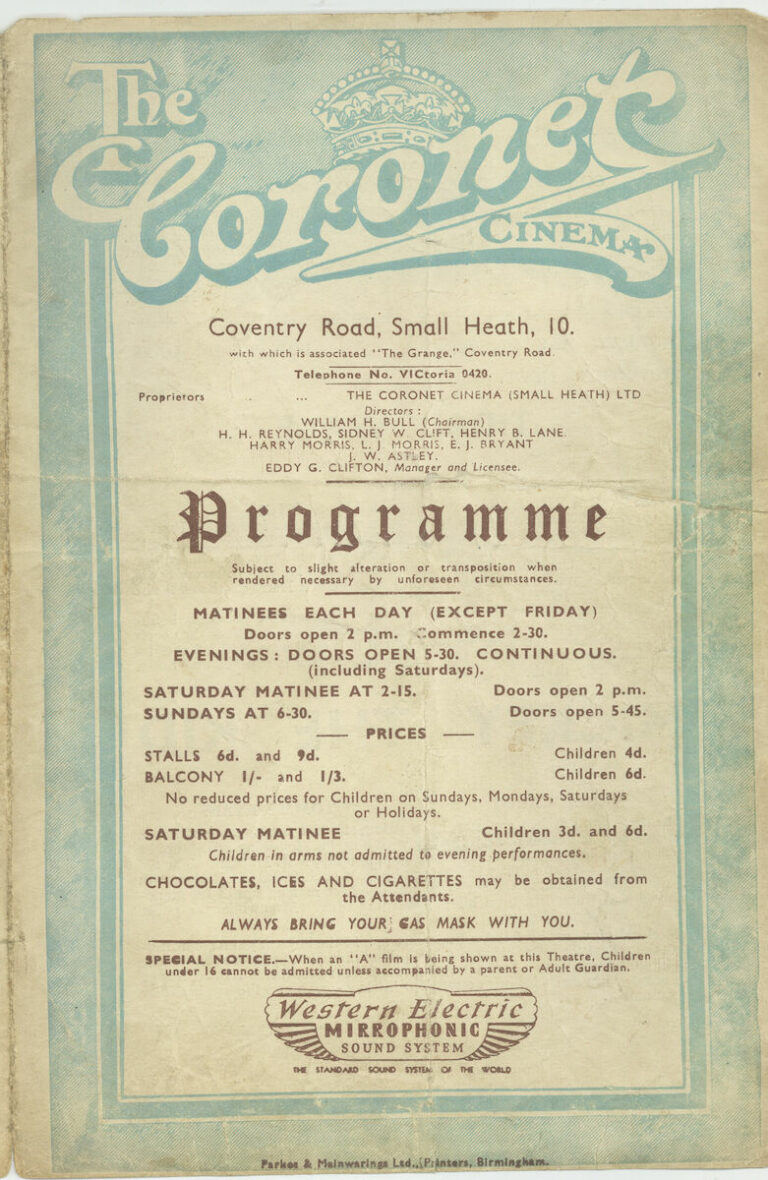

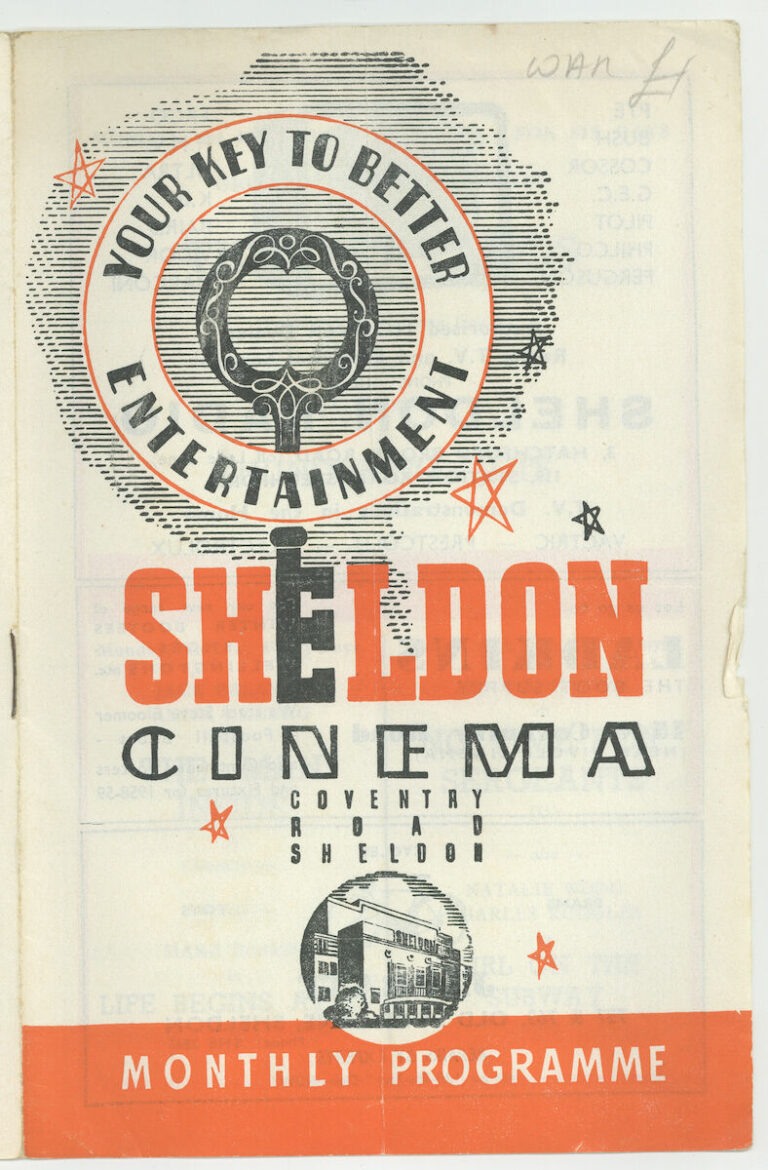

Programmes from the 40s and 50s for just four of the many cinemas along the Coventry Road.

Courtesy of the Cinema Museum

The third theme woven through the personal stories captures the collective aspects of cinema going. An outing to the cinema was an occasion to spend time with friends. Often it was also enjoyed as an intergenerational pastime with parents. However, beyond sharing the evening with those people closest to you, going to the pictures offered a profoundly communal experience.

"Small Heath at that time had a big football ground but also lots of cinemas, partly because it was a working-class area and cinema was definitely one of those spaces where you found sociality"

The meanings that were created, the sensations that were generated, and the depth of the lasting impressions formed were attributed to knowing that a common culture was being shared at that moment. The activity of watching a film with other people – a ‘group encounter’ – heightened emotions such as joy and laughter and enhanced a sense of interconnectedness. This was expressed most evocatively in the memories of going to the Saturday pictures as a child. The ‘ABC Minors’ was a weekly film club where movies made specifically for children were screened. Many of these were produced by the Children’s Film Foundation whose mandate was to ensure that children would have the opportunity to view wholesome films with content that was age appropriate.

“The cinema is the space for imagination clearly and there is a kind of anarchy in comedy, especially for kids… that idea that you could be crazy sometimes because the Minors encouraged you to cheer and shout for the goodies and the baddies and all that stuff so unlike much later it was encouraged to be part of this sort of madness. There were no parents. No adults at all. It was kids. It was a kind of imaginative freedom”

“People queued for ages. I remember standing there, queuing up as a kid and we went to children’s cinema. And screamed. Oh, we were ruffians you know! Shouting and carrying on. They were supposed to keep us in order, and they would eject a couple and then they’d give up. So, it was fun as much as anything else but it must have been frustrating for the people who went through the trouble to book the movie. There weren’t many children’s films, but I think it was the children’s film unit. They made great movies with child stars”

For these interviewees the love of the movies carried on throughout their lives and materialised in various ways outside the act of going to the cinema – itself illustrating its lasting personal impact and wider cultural significance. Jane’s love of the movies, for example, is expressed in an extensive collection of movie memorabilia and a series of diaries that she wrote between 1974 and the early 1990s as a way of documenting each and every one of her very frequent trips to the cinema. Jean’s love of the movies inspired her to get involved in the campaign to save the Kingsway cinema from closure. It had become another victim of a widespread decline that came to characterise the British cinema industry from the 1960s onwards. Ultimately the campaign didn’t succeed but Jean was able to preserve some of these threatened places, at least on film, in a series of photographs that became part of the Wonderland exhibition. For Alan, the formative role of his early cinema going days led him to impart both his extensive knowledge of film and his joy for the movies to younger generations throughout a long career as a film studies lecturer.

The Wonderland oral history project offers a fascinating glimpse into what going to the movies has meant and why these recollections are cherished by so many people. The memories and detailed narratives chronicled in these interviews leave us with a greater appreciation and deeper understanding of the significant place cinema has occupied within the lives of Birmingham’s communities, and they invite us to reflect upon our own stories.